The Day We Saved 2,147 POWs From Los Baños Prison

(reprinted from military.com)

We Are The Mighty | By James Elphick

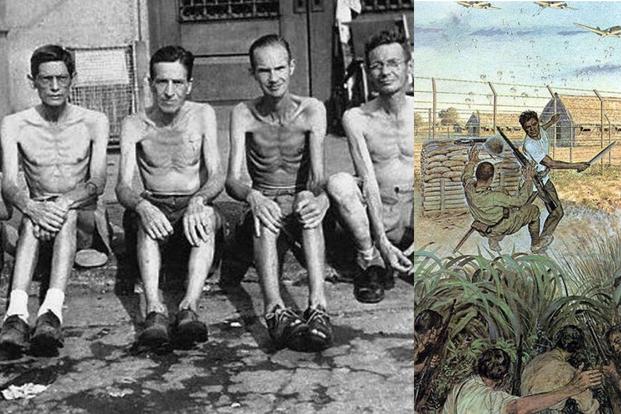

By February 1945, the cruel and inhumane treatment by the Japanese against their enemies was well known. As the Allies liberated the Philippines, the decision was made to attempt a rescue effort at the Cabanatuan Prison.

This rescue, often referred to as the Great Raid, liberated over 500 prisoners from Cabanatuan on Jan. 30, 1945. These prisoners then described their horrific treatment as well as the atrocities of the Bataan Death March.

This convinced the Allied commanders to attempt more rescue operations in order to save the lives of those held by the Japanese.

A plan was quickly drawn up, this time using paratroopers from the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment.

The target would be the University of the Philippines campus-turned POW camp at Los Baños. There the

Japanese were holding over 2,000 Allied personnel, mostly civilians who were caught up in the Japanese onslaught of late 1941.

The plan was divided into four phases.

The first phase involved inserting the 11th Airborne’s divisional reconnaissance platoon along with Filipino guerrillas as guides.

Prior to the attack they would mark the drop zone for the paratroopers and landing beach for the incoming Amtracs. Others from the platoon would attack the sentries and guard posts of the camp in coordination with the landing of the paratroopers.

The second phase consisted of the landing and assault by the paratroopers. These men were from Company B, 1st Battalion, 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment along with the light machine gun platoon from battalion headquarters company. They were led by 1st Lt. John Ringler.

Simultaneous to the landing of the paratroopers, Filipino guerrillas from the 45th Hunter’s ROTC Regiment would attack the prison camp itself.

Together these two groups would eliminate the Japanese within and the Americans would gather them for transport from the camp.

The third phase of the operation would bring the remainder of the 1st Battalion, 511th PIR across the Laguna de Bay in Amtracs. These would then be used to transport the prisoners to safety.

Finally, another 11th Airborne element, the 188th Glider Infantry Regiment, would make a diversionary attack along the highway leading to the camp. The intent would be to draw the Japanese attention away allowing the paratroopers to escape with the prisoners.

All of this would happen nearly simultaneously. The amount of coordination of forces was tremendous.

Everything was set to go off at 7 AM on Feb. 23, 1945.

The first to depart for the mission were the men of the division reconnaissance platoon who set out the night of Feb. 21 in small Filipino fishing boats. Once across the Laguna de Bay, they entered into the jungle and made their way to hide sites to wait for the assault to begin.

On the morning of the 23rd at 0400, the 1st Battalion minus B Company boarded the 54 Amtracs of the 672nd Amphibian Tractor Battalion and set out across the bay toward their landing beach.

At 0530 the men of B Company boarded the C-47’s for the short flight to Los Baños. By 0640 they were in the air toward their destination.

At 0700 on the morning of Feb. 23, 1945, the coordinated assault on the prison camp at Los Baños began.

Lt. John Ringler was the first man out the door of the lead C-47 coming low at 500 feet.

Having already marked the drop zone, the reconnaissance platoon and their accompanying guerrillas, spotting the incoming troop transports, sprung from their hide sites and attacked the Japanese guard post and sentries. Many were quickly overwhelmed.

At the same time, the 45th Hunter’s ROTC Regiment of Filipino guerrillas attacked three sides of the camp. As this was happening, the paratroopers were assembling on the drop zone and the lead elements were breaching the outer perimeter of the camp.

The assault had been perfectly timed to coincide with not only a changing of the guard shift but also morning formation for both the prisoners and Japanese soldiers.

Many Japanese were caught in the open, unarmed, preparing to conduct morning physical training. They were cut down by the gunfire of the assaulting forces.

Some Japanese were able to mount a defense but many simply fled in the face of the charging Americans and Filipinos. By the time the balance of the 1st Battalion arrived at the camp in their Amtracs, the fight was all but over.

In very short order the raiding force had overwhelmed and secured the prison.

Out on the highway, the 188th GIR was making good progress against the Japanese and had successfully established blocking positions by late morning. The sound of their battles reminded the men at the camp that time was of the essence — the Japanese were still nearby.

Due to their harsh treatment, many of the prisoners were malnourished and extremely weak. Those that could walk began making their way towards the beach for evacuation. Others were loaded into the Amtracs at the camp and transported back across the lake.

It took two trips to get all the internees across the lake and a third to evacuate the last of the assault troops, but at the end of the day 2,147 prisoners were liberated from the Los Baños prison camp. The cost to the Americans and Filipinos was just a handful of casualties — no paratroopers were killed in the raid.

Among those evacuated was Frank Buckles, a World War I veteran, who would go on to be the last living veteran from the conflict.

“I doubt that any airborne unit in the world will ever be able to rival the Los Baños prison raid,” said Gen. Colin Powell. “It is the textbook airborne operation for all ages and all armies.”